Anyone who witnessed the documentary Bill Cunningham New York (2010) knows that the veteran New York Times photographer has a treasure trove of photographic evidence of his favorite city and its ongoing evolution.

Riding about town on his trusty Schwinn, camera in hand, the octogenarian Cunningham has spent decades documenting the city’s fashions as worn by a lovably eccentric populace.

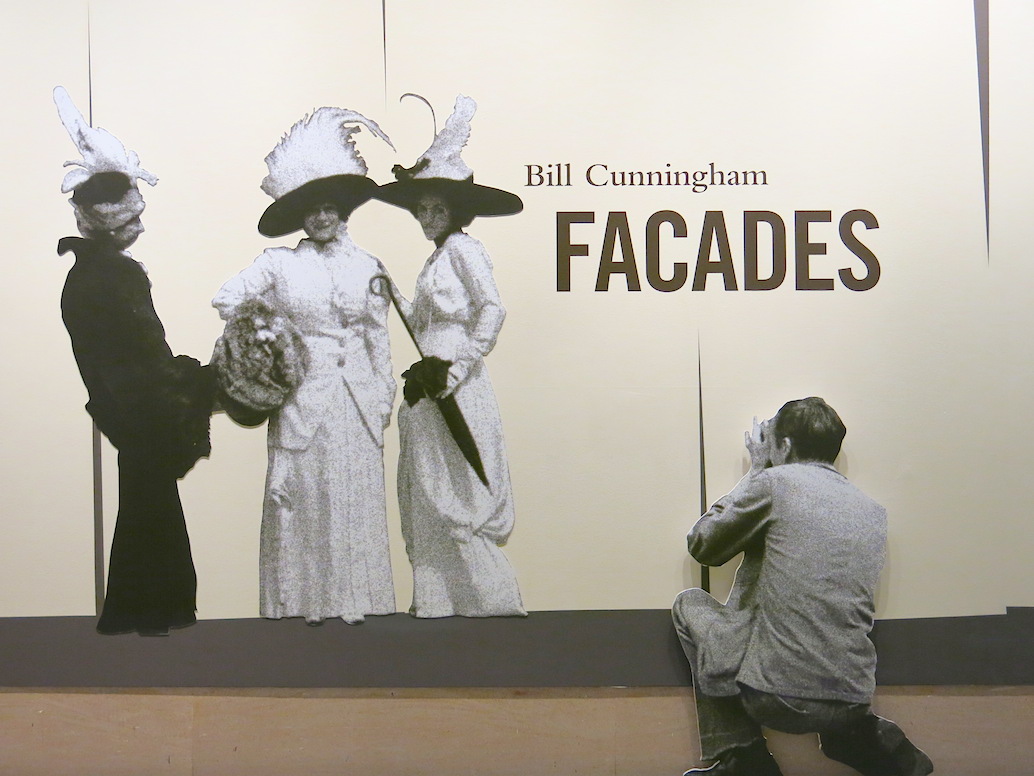

Thanks to a 1976 bequest from Cunningham of 88 silver gelatin prints, the New-York Historical Society has mounted an exhibition of Cunningham’s photographs from his Facades series that will run from March 14 through June 15, 2014 at the museum’s home at 170 Central Park West in Manhattan.

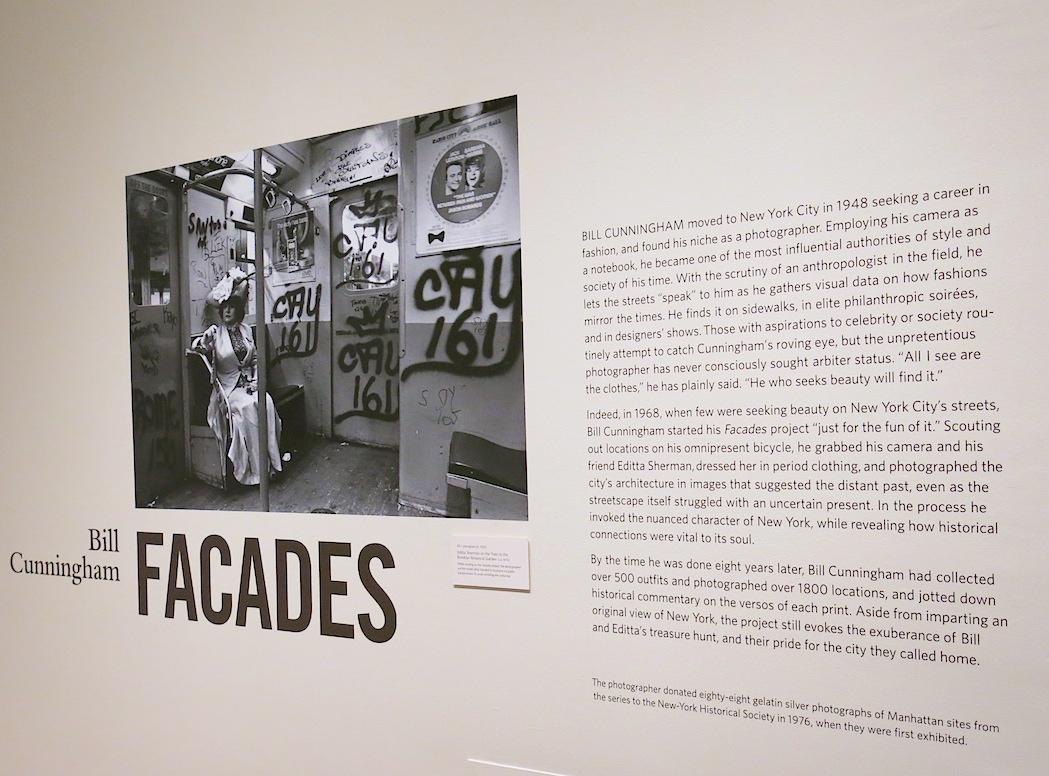

An anthropologist of all things New York, Cunningham commenced his Facades project in 1968 by scouring the city’s flea markets, auction houses, and thrift stores for vintage clothing, which he then utilized to pose models in period costumes at historic New York locales.

By the time he had completed his project in 1976, Cunningham had amassed more than 500 outfits and photographed nearly two thousand New York locations.

Apart from its focus on fashion, the eight-year project chronicled an era during which historic preservation became a cultural and political issue. (Alas, by the inauguration of Cunningham’s photographic essay, the original Penn Station had already been razed – and replaced.)

Curated by New-York Historical Society Historian Dr. Valerie Paley, the exhibition enables a re-examination of the architectural riches of New York, juxtaposed with a timeline of the vagaries of city fashions. Cunningham’s photographs capture elements of a city on the cusp of massive change and most New Yorkers will breathe with relief to see that such venerable buildings as the Bowery Savings Bank, Federal Hall, “21” Club, St. Paul’s Chapel – and yes, Grand Central Station – are still with us.

Cunningham’s commentary, dutifully jotted on the verso of his prints, attests to his immersion in the historical context of New York fashion, while also unearthing some startling facts. A model wearing a filmy dress from the 18th century while posing in front of City Hall evokes, as Cunningham writes, “the custom of the French ladies to immerse themselves in a tub of water when fully dressed so the gown would stick to the body, [which] caused an epidemic of influenza and many thousands of deaths that was called the ‘muslin disease.’”

Cunningham’s muse of that era, Editta Sherman, was also a photographer and, on the strength of these photographs, a willing and able – and ebullient – model as well. As much as anything, Facades captures the joie de vivre that Cunningham’s oeuvre has documented for decades – and his work with the zaftig Sherman is a testament to their mutual adoration for New York and each other. Witness, for example, two photographs hung alongside each other that document Sixties fashion: Sherman on a ladder in front of the Paris Theatre (which is showing Marcel Carné’s Children of Paradise) – and Sherman in front of Lever House with a grin as large as the flowers swirling on her dress and coat lining.

A photograph of Sherman garbed in 19th-century finery while sitting poised and prim in a graffiti-covered subway car beautifully mirrors the unsettling zeitgeist of New York in the late Sixties and early Seventies. As Cunningham has stated, “Fashion is the armor to survive the reality of everyday life.” This illuminating exhibition gives credence to the manner in which New Yorkers throughout history have utilized fashion to survive – and flourish.